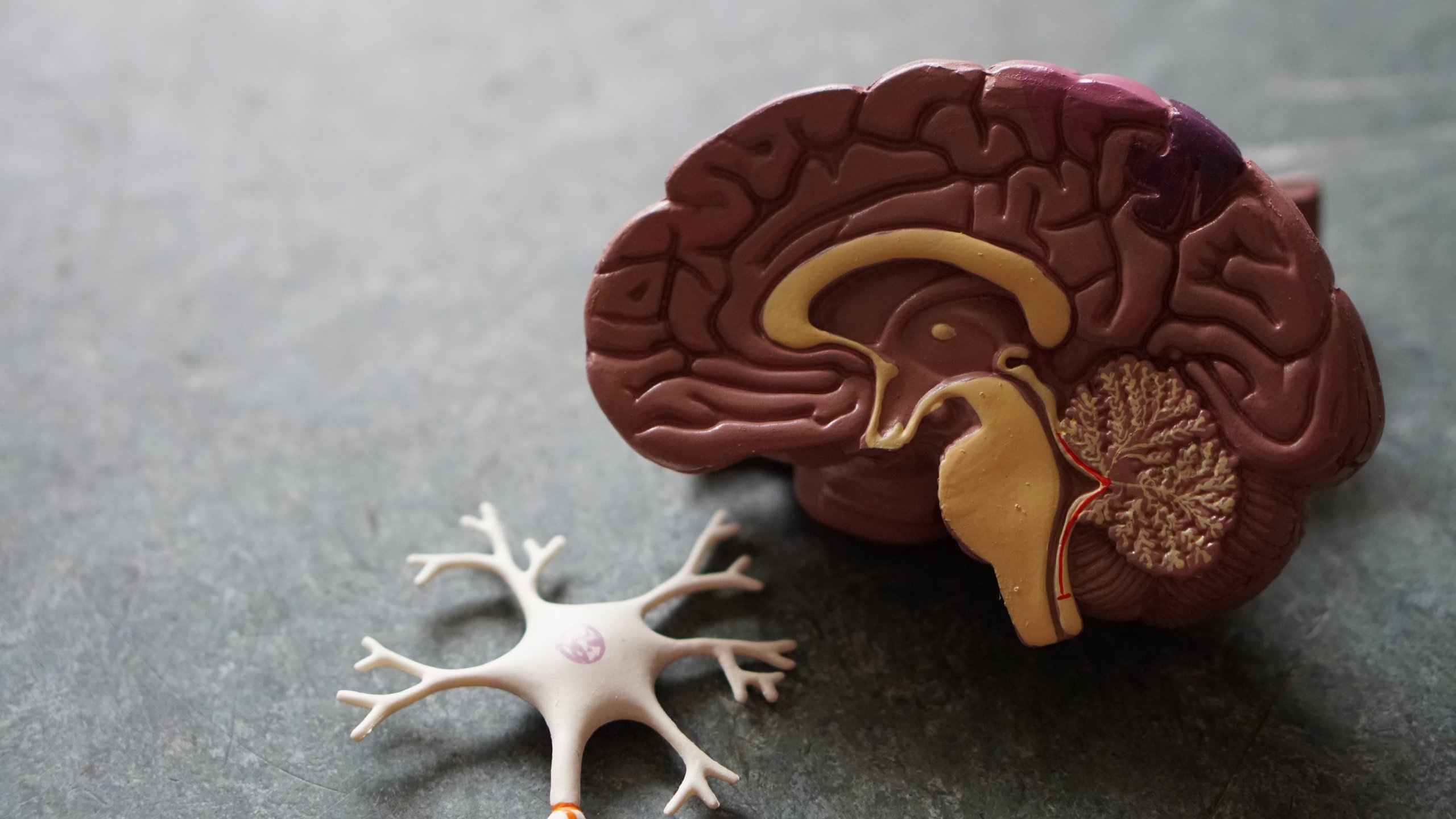

Bridging the Language and Culture Divide in Dementia Diagnosis in the MENA Region

The journey towards inclusive neuropsychology and expanding the horizons of cognitive testing means embracing cultural and linguistic diversity.

As the world grapples with the challenges of an aging population, the dramatic increase in dementia cases, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, has become a pressing issue. This surge is not just a matter of numbers: It’s a complex health puzzle where language plays a critical role, says Prof. Mohamed Seghier, Director of the Khalifa University Healthcare Engineering Innovation Center (HEIC).

“Cognitive decline, a key indicator of dementia, is typically assessed through standardized neuropsychological tools,” Prof. Seghier explains. “These tools have been effectively validated in widely spoken and well-researched languages such as English. However, a significant obstacle arises when it comes to linguistic diversity. The existing diagnostic tools fall short for speakers of less-studied languages, leading to a worrying disparity in access to early and accurate dementia diagnosis.”

Prof. Seghier and Oula Hatahet, Research and Teaching Assistant at Khalifa University, collaborated with Florian Roser from Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi’s Neurological Institute to explore the profound impact of this language gap, particularly in the MENA region. Their research delves into the challenges posed by inadequate tools and lack of expertise, considering the needs of the region’s people. Their results were published in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

“Here is a real challenge for a healthcare professional: Assess the cognitive abilities of someone speaking Hausa or Fulani,” Prof. Seghier says. “It is unlikely that validated neuropsychological tests exist for speakers of these languages, so a trained healthcare professional might rely on some available or customized translated versions. For many speakers of similar understudied languages, the context can be much more challenging than that, starting in the first place with a lack of trained professionals who can accurately administer the tests. This example is not limited to rare languages but applies to many languages spoken by hundreds of millions of people. Take Arabic, for example.”

The MENA region offers an interesting case to gauge the impact of the language gap on the assessment of cognitive decline, according to the research team. Almost half a billion people live in MENA’s 22 countries. The area has one of the highest forecasted rates of growth in the number of people living with dementia. This rise is set against a backdrop of vast socioeconomic diversity, ranging from very low to very high-income countries, and the burden of dementia on these economies is significant.

The linguistic landscape of the MENA region is marked by diglossia: Most people use modern standard Arabic for formal education and colloquial Arabic for everyday communication. This linguistic complexity raises questions about the impact of diglossia on dementia onset and assessment. The most frequently used tests are Arabic versions of the English cognitive screening tools which assess memory, attention, language and other cognitive skills. However, there is considerable variation in the cutoff values used for dementia detection in these tests, and the use of colloquial Arabic in translations poses additional challenges.

“The use of modern standard Arabic in cognitive tests could potentially alleviate some of the linguistic challenges, but its limited use among older generations and the competition from spoken dialects make this a complex issue,” Prof. Seghier explains. “Developing cognitive tests in Arabic requires consideration of cultural norms and values to avoid bias and would require involving populations from diverse backgrounds. What’s more, there is a pressing need for more comprehensive epidemiological data on dementia in the MENA region. We need significant investments to improve cognitive assessment and address the challenges associated with linguistic diversity and socioeconomic disparities.”

The research team does recognize it might not be realistically feasible to develop tests for every group and in every spoken language, and that translated versions might be the only option for some populations. However, the researchers point out that recent sophisticated machine learning architectures could support translation efforts ensuring “no language is left behind.”

“The availability of reliable and valid tests for English speakers is the result of a very active research community in cognitive neuroscience, too often relying too closely on English-speaking people,” Prof. Seghier says. “The research community in cognitive science needs to uphold inclusion by broadening the linguistic diversity of both its participants and researchers. By working on both sides of the challenge, we can offer equal opportunities when it comes to access to culturally valid and clinically useful diagnostic tools for the study of healthy and pathological aging.”

Jade Sterling

Science Writer

16 January 2024