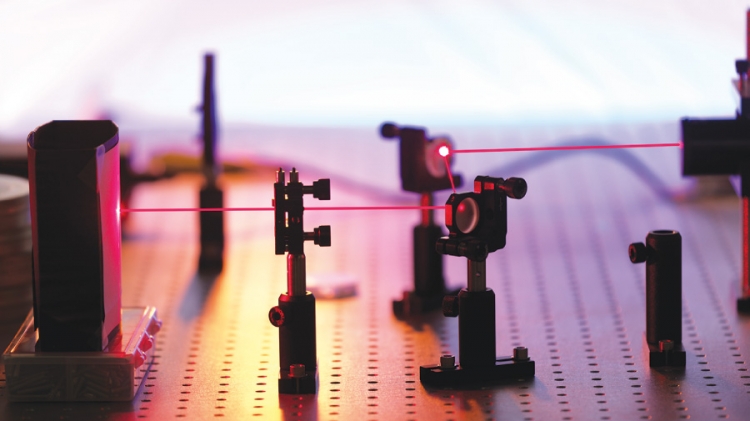

Sunlight provides Earth with a continuous stream of energy that sustains life in this planet. It lets us see, too. Not only can we see whether the fruit on a tree is an apple or an orange, the characteristics of light allows us to tell how old a star is, to probe proteins in the brain, and even detect single atoms.

At the Masdar Institute, we are taking advantage of these properties to design advanced light-sensing circuits that will help colleagues researching biofuels, solar cells, lightweight aircraft materials and more efficient desalination plants.

On one project, we are designing miniaturised chips that include lasers, optical sensing heads, micro-pumps and micro-channels, together with electronic control circuitry that can monitor glucose levels in diabetics, and diagnose asthma or even risk of severe heart failure. These chips will be made and tested at Masdar Institute, using cleanroom techniques similar to those used in making any other microchip.

We are looking at the “chemical fingerprints” left by some of these conditions – in exhaled breath, for example. These chemical compounds absorb light of specific frequencies – particularly at the two extremes of the visible spectrum, ultraviolet and infrared. Like a fingerprint, this absorption is unique, allowing us to distinguish the exact compound present.

Our project aims to design, build and test a compact and portable system that can spot the unique signatures of various gases. Such a device would have many uses. It could be used by doctors to test for diseases by checking for the presence of telltale chemicals in the breath of sufferers of diseases like lung fibrosis disorders, heart failure, asthma and diabetes.

It could also be used to monitor air quality for environmental threats to workers, like toxic industrial chemicals. Risk exposure is a serious concern in many industries, from manufacturing, to mining, oil and gas, and laboratory work.

Currently, environmental monitoring is done with devices specific to a single chemical, such as dosimeter badges for ionic radiation and personal pump-and-particle-entrapment monitors for asbestos. There is no wearable device that can monitor and measure a range of chemicals, and provide that data live to the user.

The best devices currently available – mass spectroscopy detectors – are bulky and expensive, limiting their use to only a few research labs. A portable and highly integrated optical and microelectronic system would be useful in a wide range of situations. The technology can also be deployed remotely, at site, to monitor for pollutants in the air, earth or water. This would help provide far more accurate and current data on how activities like quarrying, mining or water desalination were affecting the area around them.

The device will be sensitive enough to monitor for man-made nanoparticles, new forms of materials like metals and semiconductor particles, whose environmental effect is unknown.

Having access to this kind of data will help provide a clearer picture of the cause and effect of our actions, thus allowing for appropriate mitigation and correction.

Last but not least, having an advanced system for detecting trace contaminants will give us a better picture of the environmental effect of Abu Dhabi’s increasingly diverse industry.

The creation of such a device – and the technology it requires – could thus not only help the UAE better monitor the health and welfare of its people and environment, but also provide a useful new product to the global market, thus contributing to the country’s knowledge economy exports and intellectual property.

Dr. Jaime Viegas is an assistant professor of microsystems engineering at the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology.