- Photo Credit: The National

The new research aims to help identify susceptibility to conditions such as diabetes and heart disease

Scientists have unravelled the genetic make-up of two Emiratis for the first time.

The groundbreaking work aims to help identify people most at risk from life-threatening conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

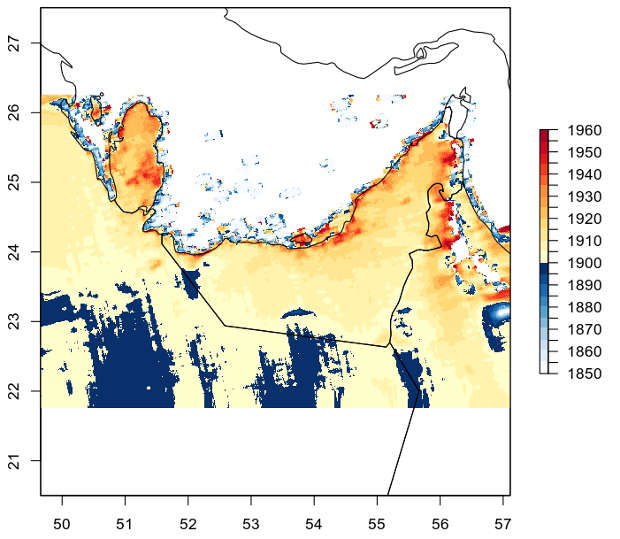

The study, undertaken in the UAE, found that the pair’s genetic material showed strong similarities to people from Central or South Asia.

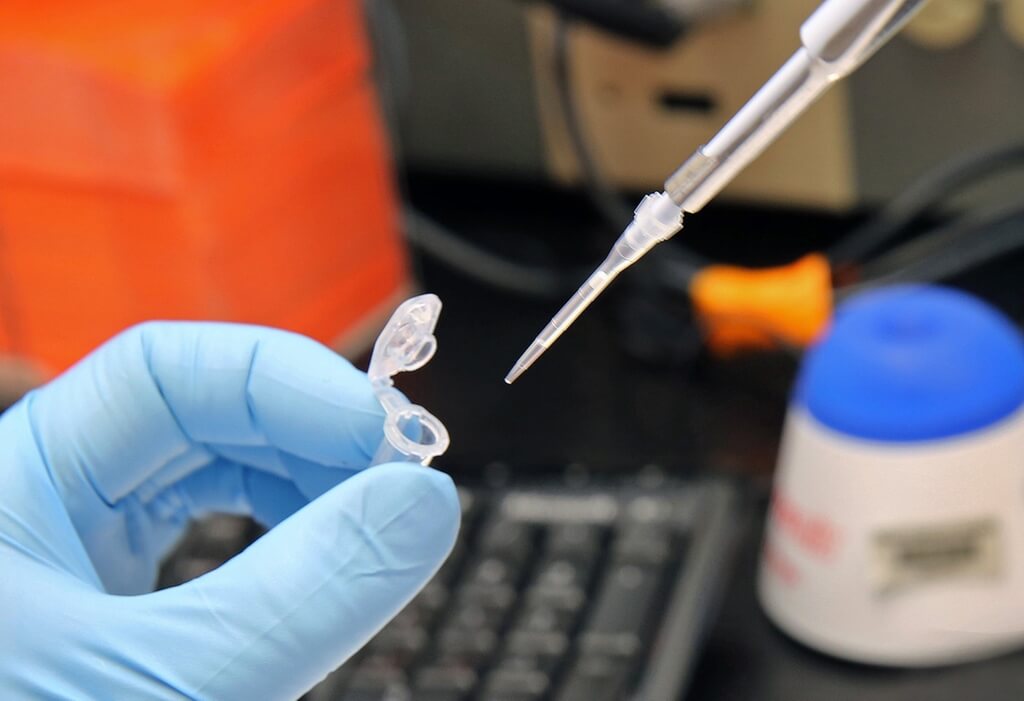

Researchers used a process known as Whole Genome Sequencing to carry out the analysis, which has never been used on Emirati citizens before.

“The information compiled will [probably] lead to the identification of target genes that could lead to the development of novel therapeutic [treatments],” the paper said.

“[It could lead to] improvements in the delivery of precision medicine, quality of life for affected individuals and a reduction in healthcare costs.”

The new research entitled “Introducing the first whole genomes of nationals from the United Arab Emirates” was published in the journal Scientific Reports this month.

It was co-authored by a team from UAE universities and health centres, including five scientists from Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi.

The two Emirati case studies, a man and a woman both aged 87, were chosen due to pre-existing medical conditions.

The male, codenamed UAE S001 by researchers, suffered from high blood pressure, diabetes and the skin condition psoriasis.

The woman, meanwhile, codenamed UAE S002, also suffered from high blood pressure.

Scientists behind the study now plan to carry out the WGS process on more Emiratis.

“This is an important first step – the first published Emirati genome,” said Dr Raghib Ali, a researcher doing related work at New York University Abu Dhabi’s Public Health Research Centre.

“It’s only by having data on tens of thousands we’ll be able to understand how genes interact with the environment.”

Other researchers also see the new work as a major step forward.

“Doing it on one or two [people] means you have the capability, the pipeline set up to do it,” said Professor Sarah Ennis, a professor of genomics at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom.

“If you can do it on one or two, you could do it in 10 or 20 or 1,000 or 2,000.”

By highlighting the gene types of a particular individual, WGS offers geneticists an insight into what diseases the patient is most likely to be susceptible to.

For example, UAE S001 was found to have genes making him more likely to develop diabetes.

Using this information, doctors can then tailor specific drug treatments to the patient’s requirements, something known as “precision medicine”.

“Not all patients respond to drugs in the same way,” said Dr Ali. “Understanding how they will react with particular individuals based on genetic make-up will be helpful.

“For risk profiling and treatment, it’s important.”

Dr. Ali said he was helping to co-ordinate the UAE Healthy Future Study, which aims to analyse the genetic material of thousands of Emiratis.

The project has already recruited 7,000 of its projected total of 20,000 participants and hopes, over the long-term, to track their medical status and help to uncover factors causing illnesses.

Starting this year, the study will carry out more basic genetic tests on all participants, while WGS will be carried out on selected individuals from next year.

Dr Ali said this would provide data indicating how genes contribute to obesity, diabetes, heart disease and, eventually, cancer in the Emirati population.

Obesity – a risk factor for diabetes – is about as prevalent among Emiratis as it is among Americans, yet diabetes is twice as common among UAE nationals.

“It suggests the Emirati population is genetically more susceptible to diabetes,” said Dr Ali.

“Through genotyping [genetic analysis] and sequencing a large population within the Emirates, we’ll be able to understand how genetic susceptibility contributes to diabetes and other non-communicable diseases.”

He said that lifestyle factors were the most critical to preventing diabetes, but understanding its genetic basis would also help.

He also argued it was vital that more genetic analysis was carried out on people from the Gulf region as there was currently a lack of data for the Middle East on the links between genes and disease.

“Once people know they’re at increased risk [of diabetes], they’re more likely to change their behaviour,” he said.

What is Whole Genome Sequencing?

Whole Genome Sequencing is the sequencing of nearly all of an organism’s DNA, our inherited genetic material.

DNA consists of a double helix (paired strands in a spiral shape), with each strand made up of chemical groups called nucleotides.

Each nucleotide contains one of four bases, each made up of carbon and nitrogen atoms as well as other elements.

The four bases are known as adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine – and their sequence determines which protein a gene produces. These proteins, in turn, control how organisms develop and how cells operate.

Only about one per cent of genetic material varies from person to person. WGS highlights these areas, even down to variations in individual bases.

This article originally appeared in The National on 22 October 2019.